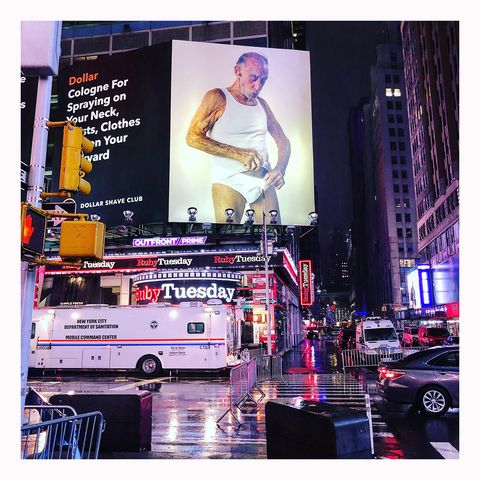

Jake Paul defeated Mike Tyson. The real sensation would have been if the result had been the opposite. But is that truly the case? Instead of commenting on the fight itself, I’ll focus on the business model concept of capitalizing on sentiment. It turns out that grand comebacks and “golden shots” are natural business models embedded in the life cycle of an investment project. Leveraging sentiment or reviving an old, well-known brand can serve as a way to extend the S-curve in Porter’s theory. Products (and undoubtedly, sports stars are also products) that evoke nostalgia and remind us of the most exciting times of our lives—when they were out of reach, too expensive, or inaccessible—sell exceptionally well when we grow up. However, this "second life" of a product is a unique offering that requires skillful marketing. Efforts directed at a singular event, such as the “boxing match of the century” or a concert featuring a band giving a one-time-only performance after 20 years, must be monetized to the fullest: a Netflix documentary, a “new” yet familiar album, or an array of merchandise. The art lies in maximizing profits from that one “shot.” The situation is different with the comeback of brands. Many iconic brands return after a period of obscurity with a new twist, achieving varying degrees of success. Retro watches, chewing gums, juices, car brands, shoes, or eyewear—all share a common goal: finding a new audience by tapping into the nostalgia of parents or guardians. Big comebacks aim to preserve the seemingly iconic appearance while integrating significant doses of modern technology. It’s like a “wolf in sheep’s clothing”—of course, in this comparison, both the wolf and the sheep carry positive connotations. Sometimes, however, companies opt for a “botox injection.” A powerful and profitable brand, threatened by a new competitor, decides to buy them out to extend its own glory. An intriguing example is Unilever. After numerous acquisitions in the shaving market (including Gillette), it faced the rapid rise of the subscription-based startup One Dollar Shave Club. This business model quickly became a hit in the U.S. Unable to compete with the phenomenon, Unilever decided to acquire the company. For a time, the company attempted to reconcile two different business models under one roof, but this proved unworkable. The values a company upholds and communicates to its customers must remain consistent. While it’s possible to own various brands catering to different demographics—wealthier and less affluent audiences, for instance—operating two business models is inefficient. Last year, Unilever sold One Dollar Shave Club to the Nexus fund. The very next day, a negative campaign began, and the iconic Gillette started regaining market share. Business botox or “powdering the nose” (not to be confused with the concept from Pulp Fiction) can be highly profitable if well-planned. However, as with any interference with “nature”—in this case, the market—it can lead to devastation and a bitter aftertaste.

show less