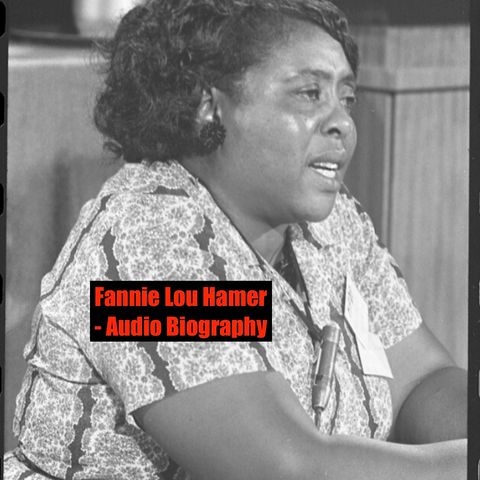

22 AUG 2024 · Fannie Lou Hamer: The Indomitable Voice of Civil Rights Fannie Lou Hamer, born Fannie Lou Townsend on October 6, 1917, in Montgomery County, Mississippi, emerged as one of the most powerful voices of the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Her life story is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the transformative power of grassroots activism. From her humble beginnings as a sharecropper to becoming a nationally recognized civil rights leader, Hamer's journey embodies the struggle for equality and justice in 20th century America. Early Life and Background Fannie Lou was the youngest of 20 children born to Lou Ella and James Townsend, sharecroppers who struggled to make ends meet in the segregated and economically oppressive system of the Mississippi Delta. Her early life was marked by poverty and hardship, experiences that would later fuel her passion for social justice and equality. From the tender age of six, Fannie Lou worked alongside her family in the cotton fields. Despite the grueling labor, she developed a strong work ethic and a deep connection to the land and her community. Her formal education was limited; like many African American children in the rural South, she was only able to attend school for a few months each year when her labor wasn't needed in the fields. Despite these obstacles, Fannie Lou demonstrated a keen intelligence and a thirst for knowledge that would serve her well in her later activism. In 1944, at the age of 27, Fannie Lou married Perry "Pap" Hamer, a fellow sharecropper. The couple worked on the plantation of W.D. Marlow near Ruleville, Mississippi. They were unable to have children of their own, but they adopted two girls, providing them with the loving home they had always wanted. Awakening to Activism Fannie Lou Hamer's life took a dramatic turn in 1961 when she underwent surgery to remove a uterine tumor. Without her consent or knowledge, the white doctor performed a hysterectomy, a practice so common it was known as a "Mississippi appendectomy." This horrific experience of medical racism was a turning point for Hamer, igniting a fire of resistance that would burn for the rest of her life. In 1962, at the age of 44, Hamer attended a meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). It was here that she first learned that African Americans had a constitutional right to vote. This revelation transformed her. As she later recounted, "I had never heard, until 1962, that black people could register and vote." Determined to exercise this right, Hamer and a group of fellow activists traveled to the county courthouse in Indianola to register to vote. They were met with intimidation, harassment, and literacy tests designed to disenfranchise Black voters. Hamer, who had taught herself to read and write, managed to complete the test but was ultimately denied registration on a technicality. Upon returning home, Hamer found that her activism had consequences. The plantation owner, angered by her attempt to register, fired her and evicted her family from their home. Undeterred, Hamer famously declared, "I didn't try to register for you. I tried to register for myself." The Freedom Summer and Beyond Hamer's courage in the face of adversity caught the attention of SNCC organizers, who recognized her natural leadership abilities and her deep connection to the local community. She quickly became a key figure in the civil rights movement in Mississippi, helping to organize Freedom Summer in 1964, a massive effort to register African American voters across the state. Her work was dangerous and met with violent resistance. In June 1963, Hamer and several other activists were arrested in Winona, Mississippi, after attending a voter registration workshop. While in custody, they were brutally beaten. Hamer suffered permanent kidney damage and a blood clot behind her eye, leaving her with a limp and partial loss of vision. But rather than silence her, this experience only strengthened her resolve. Hamer's powerful testimony about this incident before the Credentials Committee at the 1964 Democratic National Convention brought national attention to the civil rights struggle in Mississippi. In her characteristic straightforward style, she declared, "I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired." This phrase would become one of the most iconic statements of the civil rights movement. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party Perhaps Hamer's most significant political contribution was her role in founding the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in 1964. The MFDP was established as an alternative to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party, which had systematically excluded African Americans from the political process. Hamer and other MFDP delegates traveled to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, challenging the seating of the all-white Mississippi delegation. In a televised hearing, Hamer gave a passionate speech detailing the violence and discrimination faced by Black voters in Mississippi. Her testimony was so powerful that President Lyndon B. Johnson called an impromptu press conference to divert media attention from her speech. Although the MFDP was not successful in unseating the white delegation, their efforts brought national attention to the disenfranchisement of Black voters in the South. This increased awareness contributed to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, a landmark piece of civil rights legislation. Continued Activism and Later Life Hamer's activism extended beyond voting rights. She was a strong advocate for economic justice, recognizing that political rights meant little without economic security. In 1969, she founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative, a community-based rural and economic development project. The cooperative bought up land that Black farmers could own and farm collectively, providing a degree of economic independence to members of the community. Hamer also worked to improve healthcare and education in her community. She established the Freedom Farm Cooperative Community Development Corporation in 1974 to provide child care, educational services, and housing for low-income families. Her efforts demonstrated a holistic approach to civil rights, addressing not just political inequalities but also economic and social disparities. Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hamer continued to speak out on issues of civil rights and social justice. She was an early critic of the Vietnam War, drawing connections between the struggle for civil rights at home and America's actions abroad. She also became involved in the National Women's Political Caucus, recognizing the importance of women's voices in politics. Legacy and Impact Fannie Lou Hamer passed away on March 14, 1977, at the age of 59. Her death was attributed to breast cancer, hypertension, and the lingering effects of the beating she had endured in Winona. But her legacy lived on, continuing to inspire generations of activists and leaders. Hamer's impact on the civil rights movement and American politics cannot be overstated. Her grassroots organizing helped to change the political landscape of Mississippi and the entire South. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, which she helped to bring about, led to a significant increase in Black voter registration and political participation across the country. Her famous phrase, "I'm sick and tired of being sick and tired," encapsulated the frustration and determination of the civil rights movement. It continues to resonate with activists today, serving as a rallying cry for those fighting against injustice and oppression. Hamer's life story is a powerful reminder of the impact that one determined individual can have. Despite facing poverty, discrimination, and violence, she never wavered in her commitment to justice and equality. Her courage in speaking truth to power, her ability to connect with and mobilize her community, and her visionary approach to civil rights as encompassing political, economic, and social justice, make her one of the most important figures of the 20th century civil rights movement. In recognition of her contributions, Hamer received numerous awards and honors during her lifetime and posthumously. In 1970, she was awarded an honorary doctorate from Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. In 1993, she was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. Personal Life and Character While Hamer is primarily remembered for her public activism, her personal life and character were equally remarkable. Despite the hardships she faced, Hamer maintained a deep faith and an irrepressible spirit. She was known for her powerful singing voice, often leading freedom songs at rallies and meetings. Her rendition of "This Little Light of Mine" became an anthem of the civil rights movement. Hamer's strength came not just from her individual determination, but from her deep roots in her community and her unwavering faith. She often quoted scripture in her speeches, seeing her fight for civil rights as a moral and spiritual imperative. Her faith gave her the courage to face violence and intimidation, and to speak out against injustice even when doing so put her life at risk. Despite her limited formal education, Hamer was a gifted orator and strategist. She had a talent for breaking down complex political issues into relatable terms, making the struggle for civil rights accessible to ordinary people. Her authenticity and passion inspired others to join the movement, and her leadership style emphasized empowering others to stand up for their rights. Continuing Relevance Today, Fannie Lou Hamer's legacy continues to inspire new generations of activists and leaders. Her holistic approach to civil rights, addressing not just political but also economic and social inequalities, remains relevant in current discussions about racial justice and equity.